Champion Cubed

By Holly Bruce

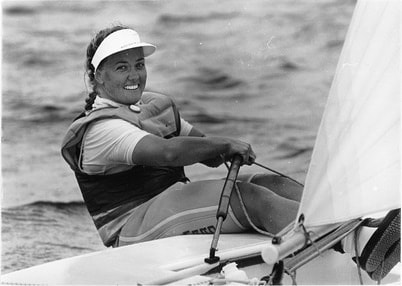

During her twenties Jacqueline Ellis traversed Europe many times. On one trip she spent three months travelling in a canary-yellow Ford Bedford. This ex-ambulance vehicle—revamped with house-paint—provided both accommodation and transport during the weeks she spent competing in sailing regattas around the continent. These events were warm-ups for the trip’s focus: the World Championships. It was a time spent with a ‘great bunch of friends’ she enthuses, ‘just living by the seat of our pants, travelling around Europe, having a blast.’

The Ellis family framework was set to support Jacqueline and her tilt toward talent. Her brother Scott also had a keen interest in sailing, and their father had been a World International Cadet Champion. So when the World Championships were held in Europe, Jacqueline and Scott—along with a slew of sailing friends—spent months tracing the same trail their English father had travelled years before.

These European adventures began in 1988—when Ellis won the Women’s World Championships in Falmouth England. Spurred on by this win and a couple of government grants, the World Championships, for Ellis, became an annual event. The European regatta road-trips continued, in colourful clapped-out Kombis and bashed about Bedfords, well into the nineties.

For Jacqueline, the competitive sailing life featured National Championships in Australia during January, mid-year trips to The Worlds—as she calls them—and an intense focus on sailing, working, and saving money in between. At an age in life when many of her contemporaries were working to buy clothes, make up, and concert tickets, Jacqueline was saving every cent she made toward her next sailing sojourn.

‘It teaches you a lot of life lessons,’ Jacqueline acknowledges. ‘You do have to be organised, you do have to work out what your priorities are. It does create a self discipline and motivation to achieve what you want to achieve.’

Jacqueline’s sailing aptitude originally found form in a secondhand Pelican Dingy at the 16ft Sailing Club in Belmont, NSW, when she was eleven years old. It was here that Jacqueline sailed her first race with crewmate Natalie Butterworth. Jacqueline advanced from the Pelican Dingy to sailing VJ’s after winning the Best Female Crew Award in her brother’s boat ‘Quicksilver.’ She began competing in the VJ’s class, on a national level, when she was fifteen. But for Jacqueline, it was the Laser that truly captured her sailing spirit. She discovered this in a shift from VJ’s to the Laser class during the year she completed her HSC. She entered her first Laser National Championship in South Australia when she was just eighteen. Heading out of Adelaide Sailing Club in Glenelg and crossing the bar to reach the bay, Jacqueline entered more challenging waters than she had previously experienced in the familiar racing courses of Lake Macquarie and NSW coastal rivers. She leaned into the challenge and was hooked. It was at this point that her Laser Life began and extended for over a decade. Continued participation in National Championships took her from Queensland to Perth to Tasmania and, soon after, she began participating in World Championships in countries including Europe, United Kingdom, Japan and New Zealand and USA.

‘I was just lucky, I think, just really lucky to have that opportunity and to have the support and the encouragement of my parents who said, what the hell, off you go.’

During the early days, whilst still living in Belmont, Jacqueline and Scott sailed at the 16ft Sailing Club on Saturdays and Sydney’s Middle Harbour on Sundays. Jacqueline then moved to Sydney where she continued to sail Middle Harbour and when her work later took her to Queensland she sailed in the Darling Point Sailing Squadron. Her life was woven around a constellation of sailing clubs and events. Laser sailing was her sport, her social scene, and her lifestyle rudder. She has been extremely fortunate, she feels, to have experienced the considerable connections, comradery, friendships, and travel opportunities that were born through her sport.

The Laser lifted Jacqueline to a new level of sailing. Much of the appeal—she says—lay with the fleet size. Laser fleets are considerably larger than those of the VJ’s. A good start in a Laser race is critical.

‘When a start line in a national competition numbers over one hundred boats, positioning your boat advantageously is crucial,’ she explains. From the start point on, a Laser race is a skilfully executed balance and integration of inner and outer elements. The course must be negotiated through analysis of prevailing water and weather conditions in conjunction with mastering the positioning of the boat to best approach and round the markers within the optimal time frame, whilst avoiding both congestion and collision. Sailing a Laser is a call to strategise and analyse, with foresight, the course, the conditions, the fleet, time, and recovery if necessary. For Jacqueline this has always been the pull of Laser sailing: the physical and the tactical challenge.

Some technical aspects of competitive Laser racing have changed since Jacqueline began racing in the late eighties. Initially a typical race structure was set to a triangular course. This meant working into the wind, with two reaches. This later changed to a trapezoidal course where the sailor would work into the wind toward a reach, followed by a dead square run, and then a second reach. In addition to course changes a further shift in Laser racing occurred during the nineties, when the full rig was replaced by the modified radial rig in women’s racing. The radial is a smaller sail and became the accepted rig in women’s competition racing.

The introduction of the Laser class as an Olympic event in 1996 saw a drop in State and National Laser sailors. The race programme altered, increasing from one race to two races per day, mirroring the Olympic structure. This lead to a reduction in time available for associated social activities which resulted in some recreational sailors losing interest in State and National events. Jacqueline accepted and accommodated changed conditions and sailed on.

Jacqueline sailed in women’s and open competition both in Australia and overseas. When home she regularly raced in open events which prepared her well for unknown international women competitors. She was not shown any mercy due to gender, a fact for which she has always been grateful. An open race always entailed ‘all guns blazing’ she says. And I would never want it any other way. ‘I’m just a sailor on a boat.’ But clearly Jacqueline Ellis is not your average ‘sailor on a boat’ and she has the cubes to prove it.

Competition awards are presented in the form of cubes in Laser sailing. The awarded cubes are made from perspex and feature the outline of a Laser. The base of the cube is coloured according to the event. The cubes are presented to the top five, sailors at Regional, State, National and World Championships levels. A symbol on the face of the cube indicates where the competitor places in the race. Jacqueline has her cubes stored in boxes in her garage and at this point in her sailing career is unsure of her cube count. As the winner of dozens of Regional and State races, eight National Women’s Championships, along with World Championship wins in 1988 and 1996—and numerous placings in between—Jacqueline clearly has talent cubed.

By Holly Bruce

During her twenties Jacqueline Ellis traversed Europe many times. On one trip she spent three months travelling in a canary-yellow Ford Bedford. This ex-ambulance vehicle—revamped with house-paint—provided both accommodation and transport during the weeks she spent competing in sailing regattas around the continent. These events were warm-ups for the trip’s focus: the World Championships. It was a time spent with a ‘great bunch of friends’ she enthuses, ‘just living by the seat of our pants, travelling around Europe, having a blast.’

The Ellis family framework was set to support Jacqueline and her tilt toward talent. Her brother Scott also had a keen interest in sailing, and their father had been a World International Cadet Champion. So when the World Championships were held in Europe, Jacqueline and Scott—along with a slew of sailing friends—spent months tracing the same trail their English father had travelled years before.

These European adventures began in 1988—when Ellis won the Women’s World Championships in Falmouth England. Spurred on by this win and a couple of government grants, the World Championships, for Ellis, became an annual event. The European regatta road-trips continued, in colourful clapped-out Kombis and bashed about Bedfords, well into the nineties.

For Jacqueline, the competitive sailing life featured National Championships in Australia during January, mid-year trips to The Worlds—as she calls them—and an intense focus on sailing, working, and saving money in between. At an age in life when many of her contemporaries were working to buy clothes, make up, and concert tickets, Jacqueline was saving every cent she made toward her next sailing sojourn.

‘It teaches you a lot of life lessons,’ Jacqueline acknowledges. ‘You do have to be organised, you do have to work out what your priorities are. It does create a self discipline and motivation to achieve what you want to achieve.’

Jacqueline’s sailing aptitude originally found form in a secondhand Pelican Dingy at the 16ft Sailing Club in Belmont, NSW, when she was eleven years old. It was here that Jacqueline sailed her first race with crewmate Natalie Butterworth. Jacqueline advanced from the Pelican Dingy to sailing VJ’s after winning the Best Female Crew Award in her brother’s boat ‘Quicksilver.’ She began competing in the VJ’s class, on a national level, when she was fifteen. But for Jacqueline, it was the Laser that truly captured her sailing spirit. She discovered this in a shift from VJ’s to the Laser class during the year she completed her HSC. She entered her first Laser National Championship in South Australia when she was just eighteen. Heading out of Adelaide Sailing Club in Glenelg and crossing the bar to reach the bay, Jacqueline entered more challenging waters than she had previously experienced in the familiar racing courses of Lake Macquarie and NSW coastal rivers. She leaned into the challenge and was hooked. It was at this point that her Laser Life began and extended for over a decade. Continued participation in National Championships took her from Queensland to Perth to Tasmania and, soon after, she began participating in World Championships in countries including Europe, United Kingdom, Japan and New Zealand and USA.

‘I was just lucky, I think, just really lucky to have that opportunity and to have the support and the encouragement of my parents who said, what the hell, off you go.’

During the early days, whilst still living in Belmont, Jacqueline and Scott sailed at the 16ft Sailing Club on Saturdays and Sydney’s Middle Harbour on Sundays. Jacqueline then moved to Sydney where she continued to sail Middle Harbour and when her work later took her to Queensland she sailed in the Darling Point Sailing Squadron. Her life was woven around a constellation of sailing clubs and events. Laser sailing was her sport, her social scene, and her lifestyle rudder. She has been extremely fortunate, she feels, to have experienced the considerable connections, comradery, friendships, and travel opportunities that were born through her sport.

The Laser lifted Jacqueline to a new level of sailing. Much of the appeal—she says—lay with the fleet size. Laser fleets are considerably larger than those of the VJ’s. A good start in a Laser race is critical.

‘When a start line in a national competition numbers over one hundred boats, positioning your boat advantageously is crucial,’ she explains. From the start point on, a Laser race is a skilfully executed balance and integration of inner and outer elements. The course must be negotiated through analysis of prevailing water and weather conditions in conjunction with mastering the positioning of the boat to best approach and round the markers within the optimal time frame, whilst avoiding both congestion and collision. Sailing a Laser is a call to strategise and analyse, with foresight, the course, the conditions, the fleet, time, and recovery if necessary. For Jacqueline this has always been the pull of Laser sailing: the physical and the tactical challenge.

Some technical aspects of competitive Laser racing have changed since Jacqueline began racing in the late eighties. Initially a typical race structure was set to a triangular course. This meant working into the wind, with two reaches. This later changed to a trapezoidal course where the sailor would work into the wind toward a reach, followed by a dead square run, and then a second reach. In addition to course changes a further shift in Laser racing occurred during the nineties, when the full rig was replaced by the modified radial rig in women’s racing. The radial is a smaller sail and became the accepted rig in women’s competition racing.

The introduction of the Laser class as an Olympic event in 1996 saw a drop in State and National Laser sailors. The race programme altered, increasing from one race to two races per day, mirroring the Olympic structure. This lead to a reduction in time available for associated social activities which resulted in some recreational sailors losing interest in State and National events. Jacqueline accepted and accommodated changed conditions and sailed on.

Jacqueline sailed in women’s and open competition both in Australia and overseas. When home she regularly raced in open events which prepared her well for unknown international women competitors. She was not shown any mercy due to gender, a fact for which she has always been grateful. An open race always entailed ‘all guns blazing’ she says. And I would never want it any other way. ‘I’m just a sailor on a boat.’ But clearly Jacqueline Ellis is not your average ‘sailor on a boat’ and she has the cubes to prove it.

Competition awards are presented in the form of cubes in Laser sailing. The awarded cubes are made from perspex and feature the outline of a Laser. The base of the cube is coloured according to the event. The cubes are presented to the top five, sailors at Regional, State, National and World Championships levels. A symbol on the face of the cube indicates where the competitor places in the race. Jacqueline has her cubes stored in boxes in her garage and at this point in her sailing career is unsure of her cube count. As the winner of dozens of Regional and State races, eight National Women’s Championships, along with World Championship wins in 1988 and 1996—and numerous placings in between—Jacqueline clearly has talent cubed.